Table Of Contents

Of all the risk factors that confront investors, concentrated-stock risk is perhaps the sweetest.

If you have this risk in your portfolio, you likely picked a stock that has blossomed in value, or you participated in an initial public offering because you were part of a team that took a company public. Either way, you have the very high-quality problem of deciding what to do with all of your profits.

In the institutional community, the decision is easy. You sell some, or all, of the stock, especially if the profit is 100% or more, and use the profits to buy something else. This reflects a belief – based on experience – that 100% gains are rare, and thus not to be trifled with. For executives with significant stock positions in their company, the exercise often reflects a desire to diversify their risk so that not all of their proverbial eggs are in one basket.

But individual investors tend to have radically different responses, and this creates sticky situations for them, and their advisors. John and Jane Investor often fall in love with their stocks. Every advisor knows this, and they know that trying to discuss the issue with their clients is often like trying to take lollipops from babies.

We see this on a near daily basis. We know of advisors with clients with positions in mid-cap stocks that have doubled in value in a year and the position is now worth in the high seven figures. We know of others who have a low-cost basis in some of the market’s most desirable, hottest stocks because they bought low. In these situations, the idea of taking profits is anathema. Advisors often wrestle with clients. Clients resist advisors. Mr. Market just chuckles; he is truly a patient, long-term investor.

Our response to these situations is simple: Remember Medarex.

The company was the hot biotechnology play some 20 years ago. A friend, someone who is now one of the most senior executives in the global securities industry, had a huge Medarex position. He bought the stock at low prices. He interviewed the chief executive, and he kept buying more and more. At one point, his position was worth about $22 million. Everyone told him to sell some stock, to diversify his holdings, and to avail himself of the various strategies for dealing with concentrated risk. But he was hypnotized by the value of his position. And then, circumstances changed. The stock began to retreat, and it kept falling, and he kept rationalizing the decline, arguing that the market was wrong, and he was right. Finally, he gave back all of his gains in the stock, and a lot of his initial investment. To this day, Medarex haunts him. For his family, the stock is a reminder of what to avoid in investing.

The Medarex story illustrates one of the great difficulties of investing: visualizing risk. Paper profits, of course, are tangible. You can see them anytime you look at your account. Risk is invisible – at least to untrained eyes.

This is often acutely true for individual investors who have no real market discipline. The cause of these difficulties is often rooted in how investors view the market. Main Street comes to Wall Street with dollar signs in their eyes. They want to turn $1 into $10, and thereby realize the mythical ten-bagger that Peter Lynch made famous in his book, One up on Wall Street, that was first published in 1989.

That’s why we think our software can help advisors help their clients by taking that which is difficult to see and converting it into a number and picture. Sometimes, pictures are more powerful than a thousand words. When clients win, advisors win, and they often win more.

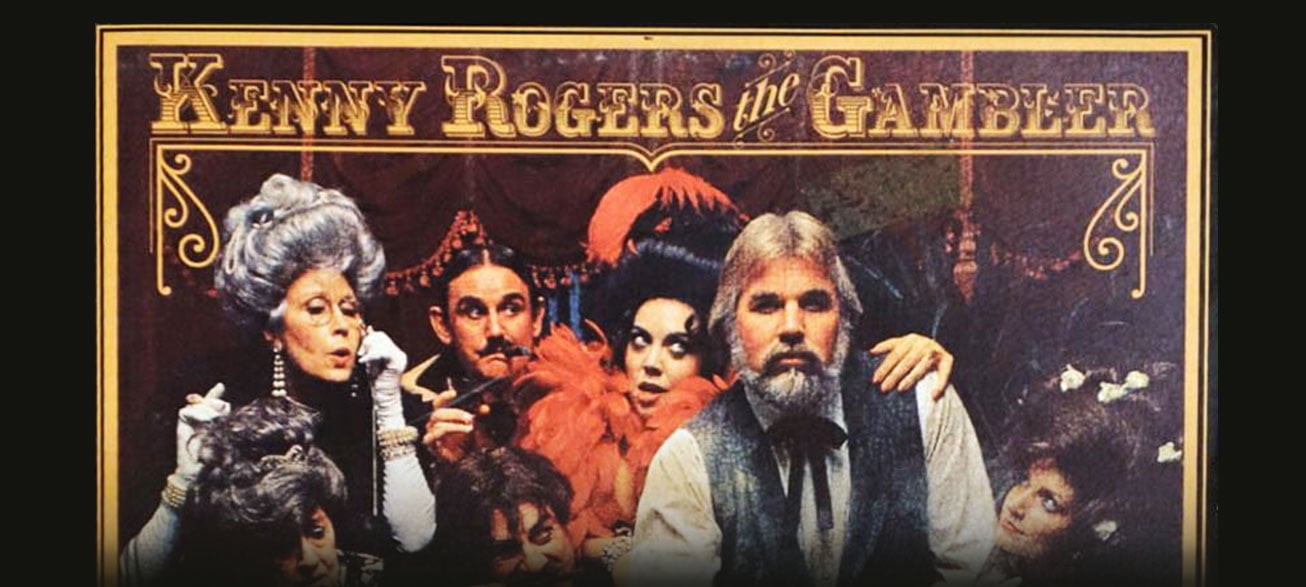

Bottom line: When it comes to investing, remember the Kenny Rogers Rule: “You have to know when to hold them, know when to fold ‘em. Know when to walk away, know when to run.” Unfortunately, too few investors ever really hear the beat of that song.