Table Of Contents

One of the market’s wise men – someone who is known and respected by everyone but shuns the limelight – believes the financial markets represent pure chaos. He contends that indexes, and exchange-traded funds and other financial products exist to provide a sense of order to the markets so the human brain does not shut down due to information overload.

Some might find his view to be extreme, but his financial chaos theory raises interesting questions.

How much control does anyone have over the market? The answer is not much. Over time, of course, stock prices rise, and thus the natural position of most investors is long. Aside from trying to let time work for you, and not against you, investors can control investment fees, and they can try manage risk through effective diversification, while resisting the urge to “greed in” at market tops and to “panic out” at market bottoms. Other than that, most everyone is left hoping that the market cycle will be in their favor when they need to convert their securities into cash.

And it is precisely because of the difficulty of timing the market that some investors feel compelled to monitor and manage risk. They do this by buying what is essentially an insurance policy for their portfolios, usually in the form of put options, which increase in value as stock prices decline. The strategy is reasonable, except it has not worked well in recent years. The stock market has steadily advanced, and any corrections have been short lived. In other words, anyone who hedged their portfolios spent money on something that they simply did not need.

Rather than engaging in the fear-mongering that is often used to persuade investors to buy hedges – a technique arguably borrowed from the life insurance industry – it’s more useful to offer a framework for discussing what is obliquely referred to as “tail risk” by institutional investors.

But first let’s define what is meant by tails.

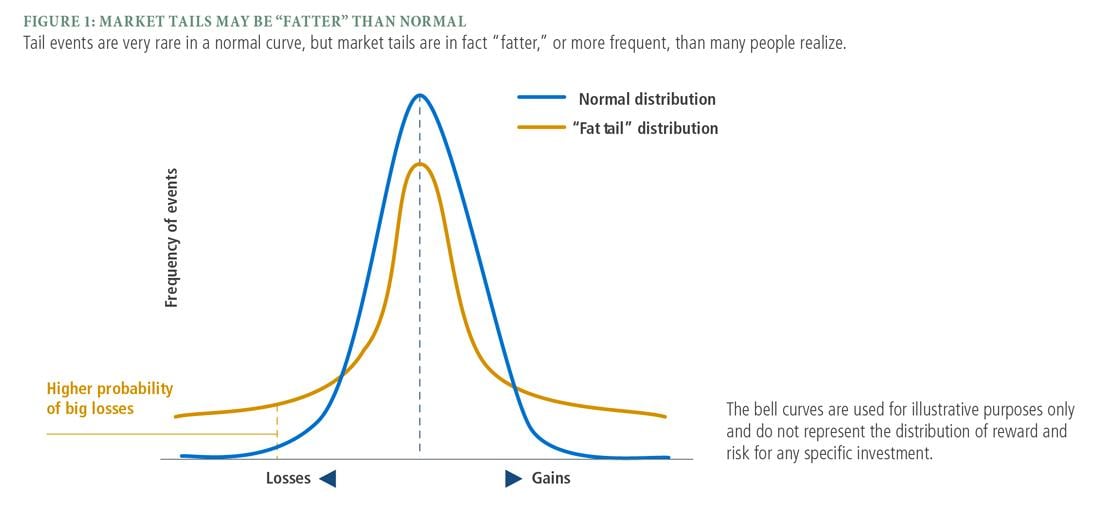

In markets, as in life, we hope that most experiences fall somewhere in the middle of the bell curve. But sometimes life and markets do not behave as we would hope. When bad things happen, that’s called a left-tail event, which is almost universally referred to simply as a “tail event.” When good things happen, investors – at least those who love jargon – talk about “right tails” to represent upside. In fact, the chief investment officer of a major bank recently told us that many clients have right-tail risks, which is to say they are underinvested in stocks.

Source: PIMCO

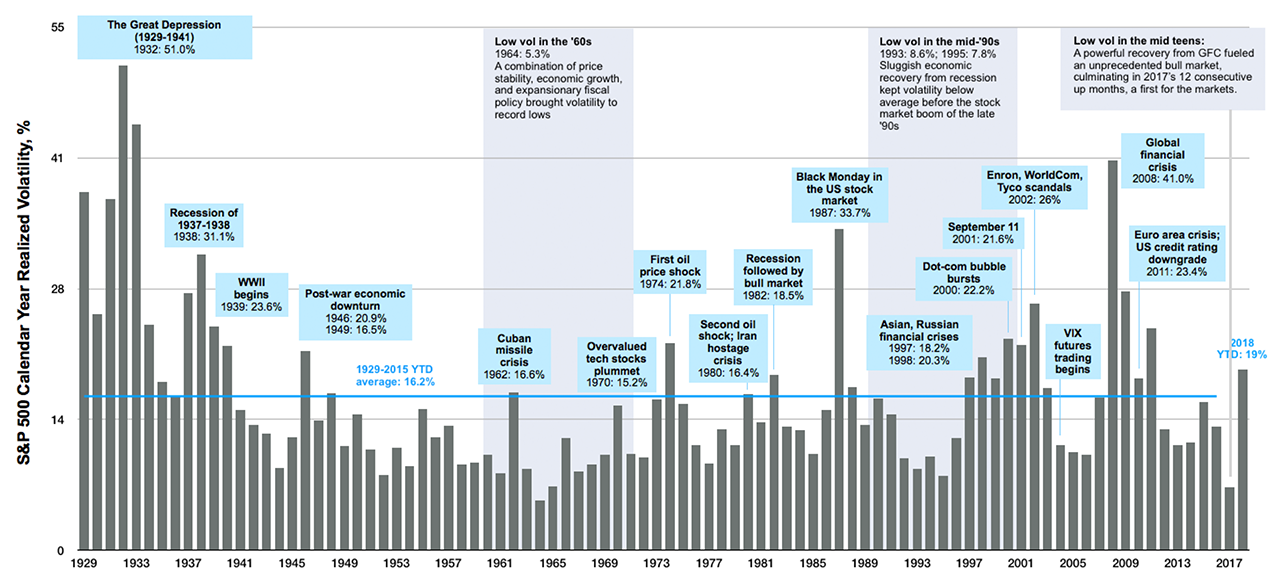

While it is easy to get lost in high-minded discussions of risk and investing, the natural question is how often do these tail events happen? They happen enough to be a legitimate concern, and something many investors monitor on a daily basis.

The second key question, however, is what happens after sharp corrections. Does the stock market snap back, and race higher, which has been true for the past decade? The third key question is personal. Do you have the risk tolerance, and fortitude, to see your investment accounts plunge in value, especially if you need access to that money because you are retired, or have other immediate obligations?

Those questions rarely get the attention that they deserve. People are busy. They are generally optimistic in their outlooks. Many do not even know to think of their investments in risk-adjusted ways, which is yet another glaring example of the difference between how money is handled on Wall Street and Main Street.

But there are some signs that this is changing. There is some debate that retirees, many of whom are living longer and have not saved enough money, should own more stocks, and less bonds, and hedge the portfolio to protect against sharp declines.

These advisors advocating hedging investment portfolios like houses or cars. Most people’s investment portfolios are worth more than their homes, or cars so they contend that it makes sense to insure them. After all, everyone buys home and auto insurance and never complains if they never need to use them. On the other hand, investment hedging can be expensive, and though the cost can often be reduced, or eliminated, investors give up potential future gains.

Perhaps the Solomon-esque solution to these issues is to simply determine if your portfolio is exposed to tail risk. After learning that, you can better decide what makes the most sense. After all, as the great philosopher Francis Bacon wrote so long ago, knowledge is power.